THE AMAZING GENESIS OF MY”ARK IN TOLEDO” STORY

PART II (see Part I here)

At this stage, I should state that I was never your average atheist, either in texture or flavour.

If I tell you that I’ve often found the likes of Jonathan Miller and Richard Dawkins to be a little too agnostic and lacking in conviction for my liking you get an idea of my feelings about all things ‘divine’, ‘spiritual’ and / or supernatural. In fact, my anti-theism—for that’s what it truly amounts to—came upon me in a sort of revelation and in a synagogue of all places, back in 1975, when I was fifteen years old.

You see, it’s not that I had always been of this mind set.

After eight days of life I’d had the obligatory encounter—for Jewish males—with the small but extremely sharp knife followed by the typical albeit fairly gentle in my case, conditioning of the traditional North London Jewish upbringing.

There was the Jewish education, both at school and at home from my observant grandfather—my ‘Zaida’; the weekly Saturday visits to synagogue (the orthodox type with the ladies sitting upstairs); the Friday night dinners; the candles and; the very many holy-days and holidays.

In fact, for the first ten years or so of my life, seduced as I was by the numerous attractions for a child of my religion, both holiday-wise and culinary-wise, I veered somewhat towards being a rather pious little boy. It probably also had a lot to do with the fact that my “most favourite person in the whole world” was indisputably my gentle, kind and incredibly dignified Zaida and that my greatest fear in those days, was doing anything to upset or disappoint him.

Thus it was, during those long tedious hours on Saturday mornings, sitting next to him in synagogue, I never gave him an inkling of how abjectly bored I was for fear of hurting his feelings.

My mildly burgeoning piety notwithstanding, in retrospect I guess, this was my first taste of what ‘duty’ meant. I suppose now, that this innate sense of duty to my grandfather had a lot to do with the fact my father had abandoned us (my mother, my one—older—brother and I) when I was six months old and that it was to my Zaida that I both looked and found that male authority I naturally craved.

However, in 1970 when I was ten years old my mother took my brother and me to live in Israel. And, although this adventure turned out to be abortive with us returning to London barely six months later, the experience delineated the end of the first and the beginning of the second chapter of my life. Paradoxically, this dalliance with life in the ‘Holy Land’ was the catalyst which began my drift away from ‘belief’.

For starters, my mum was irreligious herself and while she had been happy to ‘keep a kosher home’, with all that that entailed, during the years of our extended family existence, she lapsed almost the moment we arrived at our new home in Israel.

Suddenly, there was no more synagogue, no more Friday night dinners, no more observance of any kind. Even on Yom Kippur, we spent the day on the beach with a large picnic.

Mum felt free from the ‘clutter of observance’ for the first time in many years and her sense of freedom must have been infectious, because it transmitted itself to her two sons.

Hitherto, neither of us had ever thought to question the structure of our lives as Jewish boys. After all, it was all we knew and seemed as natural as breathing or eating.

And all of a sudden, spending Saturday mornings body-surfing on a Mediterranean beach instead of being in a stuffy synagogue surrounded by old men (they all seemed old to me at that time) chanting prayers, was very powerful medicine. And like our mum, we instinctively felt as if we had been liberated from what had been before.

But then, still only in my eleventh year, as suddenly as I had left, I found myself back in North London. And once again on Saturday mornings, I was sitting by the side of my still-adored Zaida―only now, far more dutifully than I ever could have imagined just six months previously.

But the seeds of my atheism were planted and from then on the germination was steady and relentless and it was only around five years later that I found myself on my own in another synagogue—the one belonging to my school where I was then boarding in deepest Oxfordshire.

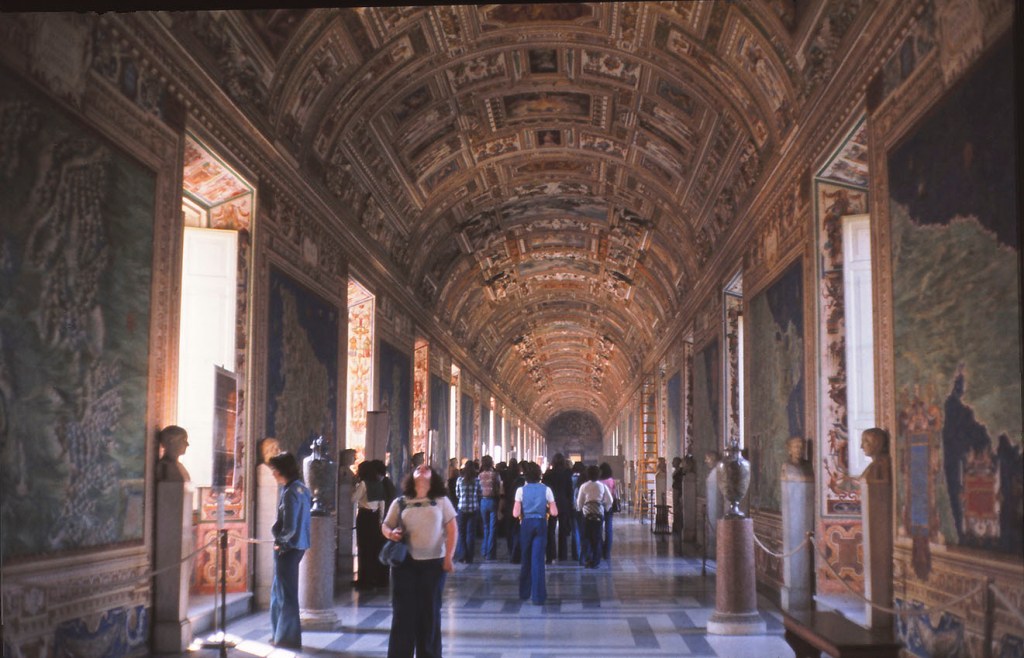

Unfortunately, I can’t recall exactly the reason why I had decided to go and sit alone in the synagogue, except that it was one of those exquisite and magisterial settings with which my old school was bounteously blessed, both geographically and architecturally (see photo above). It must have seemed a natural place to go for a troubled soul.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the building itself was one of the most remarkable and beautiful modern constructions in England.

It was designed by an inspired local architect called Thomas Hancock and you feel that when he was given the brief for the project he was also given more or less free reign, for what I presume was his one and only Jewish house of worship.

Unkindly nicknamed ‘the ski slope’ by most of the boys, it was a soaring structure of primarily glass and honey coloured timber with a grey metallic roof. At its western end it was only about twelve feet high, with the ceiling arcing upwards until it reached somewhere near sixty feet at the eastern end—hence the ‘ski slope’ analogy.

The roof was a marvel, supported by half a dozen exposed, curved, mighty wooden beams, which at that time were the longest of their kind anywhere in Europe.

Outside and within the eastern wall was formed of bare sand coloured breeze blocks. Set in its centre, an ark (the cupboard that housed the scrolls of the Law—the Torah) marked out by a pair of enormous cedar wood doors constructed of overlapping panels and flanked at its corners, from floor to ceiling by a pair of narrow jazzy, Chagall inspired stained glass windows.

The north and south walls of the synagogue were entirely of glass set in delicate wooden frames, which, especially on the south side, allowed for a broad view of the Mongewell Brook that ran through the school grounds until it spilt, via a willow fringed lake, into the River Thames.

The interior space was so conceived by Hancock, that the worshipper experienced a strong sense of exposure to, and oneness with, the landscape that the synagogue inhabited.

The afternoon in question (it was an afternoon, in case I forgot to mention) was a glorious early summer’s day.

Tall oaks, beech and cascading willows rubbed shoulders with the glazed sides of the synagogue, resplendent in their crisp, young foliage. The brook sparkled like a thousand sapphires through the glass. Assorted waterfowl frolicked, floated and bobbed about on its surface silhouetted against the silvery sheen.

I’d taken a seat on one of the long padded benches, about half way towards the ark, when almost immediately I experienced a most curious sensation.

I remember that I was looking out the south window to my left, at the above mentioned sensual, watery, Arcadian idyll beyond when, in a matter of seconds it was as if a great and terrible burden had been lifted from my shoulders.

This sensation of release caused my neck to reflex so that I found myself looking straight up at the highest part of the ceiling where the great timber roof-beams slotted neatly into their steel cradles in the lofty cool shadows.

And at that moment I was overcome with a feeling of the purest joy. I recall that I couldn’t stop smiling. I guess that I was feeling something similar to when you are told you have been cured of a terrible illness.

But, in my case, immersed within a symbiosis of man-made and natural beauty in perfect harmony, I’d come to understand with total certainty, that there was no God.

So that was how atheism came upon me and why I knew that the voice that spoke to me that night in Bossòst was the creation of my own overactive mind.

Nevertheless, despite my non-belief, I had a profound interest in the ancient history of my people. So much so, that had it not been for the fact that my aptitude for drawing and painting led me towards a less academically arduous career in the arts I would have definitely ‘done something’ along the lines of archaeology.

But despite this, by the time of my dream-like event in northern Spain I was steeped in the kind of vast general knowledge of a subject that is the special preserve of the amateur enthusiast.

So, I of course knew that according to various biblical texts the ‘Sons of Kohath’ were a high caste clan of the priestly tribe of Levi, supposedly designated by Moses to take care of—amongst other things—the Holy Ark.

Being a Levite myself I had always found this a thrilling concept.

Back in the ancient day though, being a Levite wasn’t merely a paternally handed down title like it is now with a few synagogue related duties and privileges. Back in the ancient day being a Levite really meant something and it didn’t get any more meaningful than for those of the House of Kohath.

So it was hardly surprising to me, just mere moments after the initial shock of the dream had worn off, that my vanity should have decided that I was of such an esteemed caste.

By the same token, I was equally steeped in the subject of the Ark itself; not you will gather because I believed it to be a ‘transmitter to God’, as the evil Belloq described it so eloquently in Raiders of the Lost Ark but because I agreed with Indiana Jones’ original summation at the beginning of the movie; that if the Ark had really existed and was still around somewhere today, it would be of inestimable archaeological and cultural/historic interest and value.

However, when it came to the history of the Jews of Spain and their synagogues I was far less clued-in. I had no knowledge at all about any architectural heritage they may have left behind, in Toledo―or anywhere else upon the Iberian Peninsula.

I had some sketchy ideas about the great cultural flowering of Iberian Jewry during the middle ages and, I also knew that the whole thing came to a terrible end under the Inquisition of Torquemada during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella. But, the shameful truth was, most of what I knew about the ‘Spanish Inquisition’ came from Monty Python rather than from the pages of text books.

That was why, when Dido asked me for the second time that night in very underwhelmed tones, if the word of God had meant anything to me, I replied, somewhat defensively; ‘Well, some of it means something to me.’

‘Some of it’? There’s hardly anything of it!’ she responded mystified.

‘There’s enough to mean something.’

‘You also said it was dreadful. What’s the dreadful part?’

‘Having God speak to you is pretty dreadful I would say…in the dark… in a strange place. When you’re asleep you don’t realise it’s only your own subconscious. And then there’s the Ark, the Ark of the Covenant…’

‘Okay. All very thrilling you say, but so what? Are you telling me that your subconscious mind might truly be onto something? That somehow, somewhere, you picked up the answers to the greatest archaeological mystery in the world without realising it?’

‘I’m not saying anything. I haven’t said anything.’

‘But you’re thinking it, aren’t you? You’re toying with the idea.’

‘Well of course I’m thinking about it. I’ve never encountered anything like this in my life before. It was the most intense thing I’ve ever experienced.’

‘Okay then. What do you intend to do about it? Are you going to follow it up?’

‘It’s a question of joining up the dots.’

‘Dots! My dear sweet Adam, there are no dots…’

‘Yes, there are dots. Two bloody-great-big-dots―the Ark and a synagogue in Toledo!’

‘Okay! Two dots! But then how hard can it be to join two measly dots?’

‘Very hard, when the two dots in question are separated by more than two and a half millennia by over two thousand miles. Very, very hard!’

*

And as things turned out I wasn’t wrong about that strange night in Bossòst.

It took me more than twenty years to join the two dots and come up with a plausible story of the Ark of the Covenant and a synagogue in Toledo.

Two decades of marriage to Dido and nearly as long living in Spain provided me with the confidence and the intellectual mechanics for completing this modern tale:

A tale set in a land of sublime contradictions and insane history;

A tale concerning a venerable building that represents and reflects all of that in a sublime structural form and;

A tale about a legendary artefact with an uncomfortable, not to mention highly inconvenient message.

My novel, ARK is that story…