The artistic shaping of visual perceptions of, and sensibilities towards biblical events and personalities from the Biblical era to the present day…

Since the publication of my book on King Saul of Israel (2007) I have had many invitations from academic institutions and various study groups and organisations – in person and online – to talk, both about the book itself and related subjects. Of all those talks and occasions, the one I enjoyed the most was the illustrated lecture, adapted and presented here in essay form and in several instalments, originally delivered at the University of Texas, San Antonio in the autumn (or should I say fall) of 2015.

introduction

The first thing I should do is explain for those who might not be aware, that by trade I was and have been at various stages of my life — and to varying degrees of success — an artist, a commercial illustrator, a commercial photographer, a picture framer, a viticulturist, an amateur Bible scholar and author and most recently, a novelist.

The common thread that runs through all these incarnations, professional, semi-professional and amateur is that I have retained what I refer to as the freedom to obsess — that is the near-absolute liberty to concentrate on, and devote time upon a given subject or theme in a way impossible for most contemporary working teachers and professors.

I need look no further than my own wife — an internationally respected and acclaimed researcher and teacher in her own field to see how little time she has to devote to her chosen areas of study. It’s actually quite frightening to the disinterested observer how constraining an academic career, especially a successful academic career can be today. While someone like me, an amateur outsider and a hobbyist in many respects, has nearly boundless time to explore a subject in all its minutiae, free from all distractions.

Until relatively recently in historical scholastic terms, the counterargument was that without access to the kind of university libraries and extensive research tools available to full-time scholars the chances for amateur enthusiasts to make any meaningful contributions to academic debate were negligible at best. But now that everyone — at least in the free world, has access to a virtually infinite resource for research and learning called the Internet, that argument, weak and mean-spirited then, has been completely nullified.

I would even suggest that the modern Renaissance man or woman, and the contemporary polymath might not feel more comfortable today off campus, free from the current obsession with specialisation and, as I said above, free to obsess.

In any event, this presentation, I hope will reflect my own status — or non-status if you prefer — if not as a Renaissance man or polymath, at least as that of the typical amateur scholar of the early 21st century.

In effect this will be a broad discussion of my observations with regard to the relationship of the visual arts, culminating with cinema, to and with the biblical texts that inspired them. I very much hope that my contained ramble will throw up and or provoke several points of interest.

1 images of god

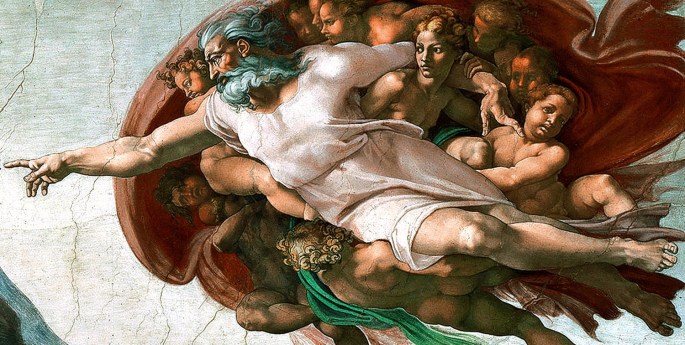

Talking of Renaissance men and women, I wonder how many people reading this, when they first see the word “God”, instinctively — in that first instant — think of something or someone like the famous Michelangelo fresco above? At least when I was a child, back in the 1960’s this would have actually been, or closely approximated to most western people’s conditioned reflex, instinctive mental image of God and had been the case since Michelangelo unveiled his Sistine Chapel masterpiece in the early 16th century.

Of course, being a product of a traditional Jewish background, raised to believe that God was formless and omnipresent this wasn’t mine or most other people’s intellectual idea of God. Yet, this image was and remains the first that fills my mind’s eye the instant I hear or think of the word “God”.

One might almost say that for millions of people, of all western creeds and cultures Michelangelo actually created our image of God, which is ironic when one remembers that this fresco detail was his interpretation of the passage from Genesis where the text informs us that God created Man in “his own image” and that it’s pretty certain that there’s a good dose of self-portraiture in the God figure — which brings me to the answer of the question posed in the title of this presentation, which must be yes, or at least this was a man who kept himself in fine robust shape, and allowing for the fact that he aged himself by around 25 years in his God portrayal. So again yes, if not actually God, what has become our instinctive mental image of God certainly seems to have paid regular visits to the local Florentine and Roman gymnasiums.

In historical terms, Michelangelo’s unforgettable, human, intimate, and yes, muscular picture of God was indeed a creation in and of itself. For before this moment, from centuries earlier and then right up until the Sistine Chapel ceiling unveiling, the God of the Church had typically been depicted as a stiff, erect, king-like figure, normally enthroned like this rather sad looking chap from a late 15th century German painting…

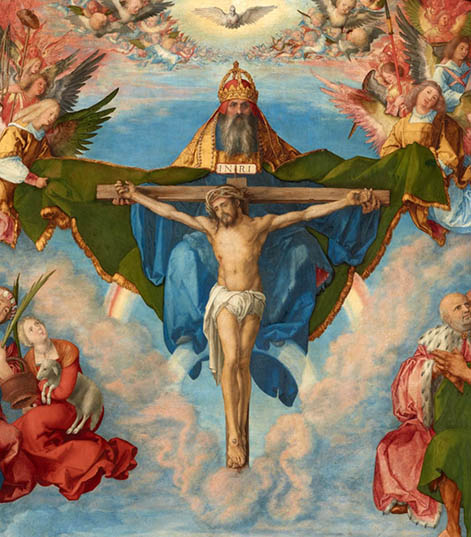

Perhaps the most graphic evidence of just how original Michelangelo’s God depiction was, and remains, is this detail from Adoration of the Trinity by Michelangelo’s most eminent non-Italian rival, Albrecht Dürer. Unveiled in the same year as the Sistine Chapel, Dürer’s God the Father has barely altered from his Iconic medieval style rigidity and austereness…

Then if we travel back both in the time and eastwards geographically to the birth time and place of the Abrahamic God – the eventual God ostensibly shared by the three Abrahamic faiths – we find God looking very different again, both in the male form of Baal…

…and the female form — or as Baal’s consort Ashtaroth or Astarte…

It’s a pretty safe bet that our Canaanite and / or our early Israelite ancestor’s visualizations of God approximated to these male and female images in the same way as ours continue to do vis-à-vis the Michelangelo representation, and that up until that ultimate representation it does seem that it was the contemporaneous conditioning of the given age and time which shaped our visual imaginings of the Divine. Incidentally, it says much for the utter genius of Michelangelo that his image, unlike all those that preceded it, has remained fixed as the conditioned reflexive image of God some 400 years after he painted it.

This factor, by the way — what I refer to as contemporaneous conditioning — is one of the key threads to this essay. The question of God’s visual identity is a big deal across the entire history of the Abrahamic faiths. It’s a question as ancient as the faiths themselves and many of today’s scholars would argue that the question actually predates formal Judaism by many centuries. In fact, we only have to consider this famous plea from Moses himself to God in Exodus 33: 18;

18 Then Moses said, “Now show me your glory.”

19 And the Lord said, “I will cause all my goodness to pass in front of you, and I will proclaim my name, the Lord, in your presence. I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I will have compassion.

20 But,” he said, “you cannot see my face, for no one may see me and live.”

21 Then the Lord said, “There is a place near me where you may stand on a rock. 22 When my glory passes by, I will put you in a cleft in the rock and cover you with my hand until I have passed by.

23 Then I will remove my hand and you will see my back; but my face must not be seen.”

The first time I read this passage I couldn’t have been much older than nine or ten years of age but I can still remember the sheer thrill I felt at the idea that Moses was as curious as I, a small child, about the appearance of God.

What particularly struck me about the passage was the pathos and that Moses’ request was so natural and normal given the extraordinary circumstances of the narrative. That the great Lawgiver, and for Jews at least, the Bible’s greatest personality, and of whom the Deuteronomist later claimed in direct contradiction to this part of Exodus, “knew the Lord face to face”, among all the signs, wonders and revelations was still desperate to see what this God actually looked like. Sadly for me and for Moses he never got his wish. But the important point here, is that this curiosity over the visual appearance of God has endured from the time of Moses until today.

What makes this especially interesting and unusual as universal obsessions go is that for two of the three Abrahamic faiths (Judaism and Islam) — officially at least — not only is God formless, it’s actually heretical to portray him pictorially. In fact, the “him” bit is the only thing that all three faiths actually agree upon, formless or not. The perversity of the concept of a formless him doesn’t seem to occur to many pious traditional teachers, at least it didn’t to the rabbis and religious teachers who informed me about this stuff.

Fortunately though, for all of us, Christianity never shared this fastidiousness with regard to portraying the likeness of God. Primarily due to its deeply Roman cultural heritage, from its earliest days, Christianity relied heavily upon sacred icons and symbols to promulgate the faith. Moreover, many of the Church’s earliest icons and religious imagery were virtually lifted from Roman originals and heavily flavoured everything that followed well into the late Middle Ages in both western and eastern versions of the faith.

This early tradition of pictorial dissemination and absorption of ideas and narratives and most importantly in our context, imagery, from host cultures has served Christianity well down the ages, and been one of the main secrets of its success in its spreading throughout the globe.

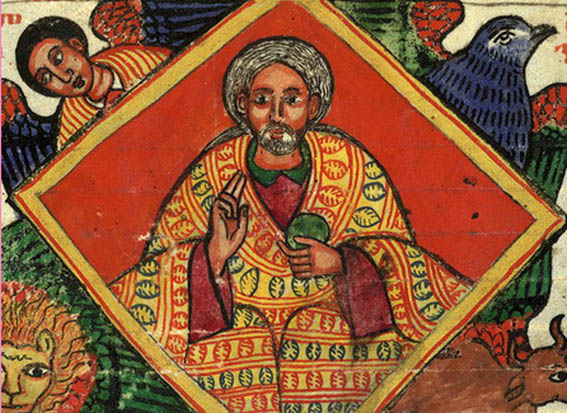

Here for example is an ancient Ethiopian portrayal of God…

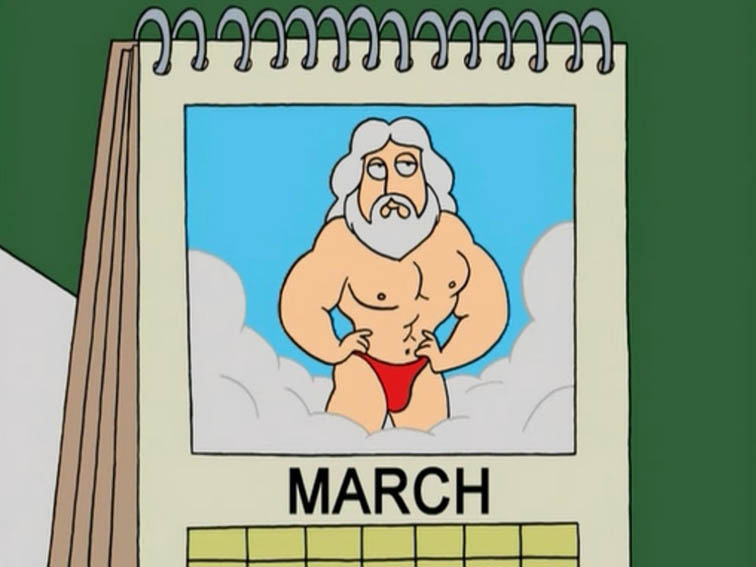

So far as western Europe was concerned however, God’s pictorial evolution reached its apogee upon the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and practically every depiction of him since then until American Dad has used it as a template — three-fingered hands notwithstanding!!

It is tempting to put this fact down to the sheer genius of Michelangelo’s painting, that a kind of perfection had been reached there were of course other important factors at work — religious and intellectual.

By this time the reformation was just beginning in Germany, beginning the spread of a heavily iconoclastic form of Christianity which seemed to revert back towards a more — one could almost say Judaic — abstracted version of the Deity. This, followed more than a century or so later by the Enlightenment with its subsequent rise in intellectual sophistication meant that God, and his appearance, was considered in a more complex way.

Yet, despite this, I’m prepared to speculate that mention the word God to anyone from Isaac Newton to Darwin and Einstein, and even the likes of Shulamith Firestone and Richard Dawkins, their initial, involuntary, instant image of God will be something like this…