In 1978, my oldest friend Simon and I spent the summer as volunteers on a kibbutz in northern Israel. Although our labour was voluntary we were paid a weekly amount to cover basic needs such as cigarettes, booze and staples from the kibbutz general store. Fortunately, we didn’t smoke; the beer was cheap, and we were sufficiently content with the food produced in the members’ dining room that we’d spent relatively little, and by the end of the stay had a reasonable amount of money saved up. We decided to pool our savings with another couple of English guys, Tim and Ben, hire the cheapest car available (which happened to be a typical 70’s yellow Fiat 127) and drive down south to spend a week in the Sinai Desert.

The Sinai was still under Israeli rule back then, free to roam almost all the way to the edge of the Suez Canal. Little did we appreciate then, that a uniquely peaceful era in the modern history of the Sinai was nearing its end and that we were about to enjoy privileged access to virtually the entire peninsula.

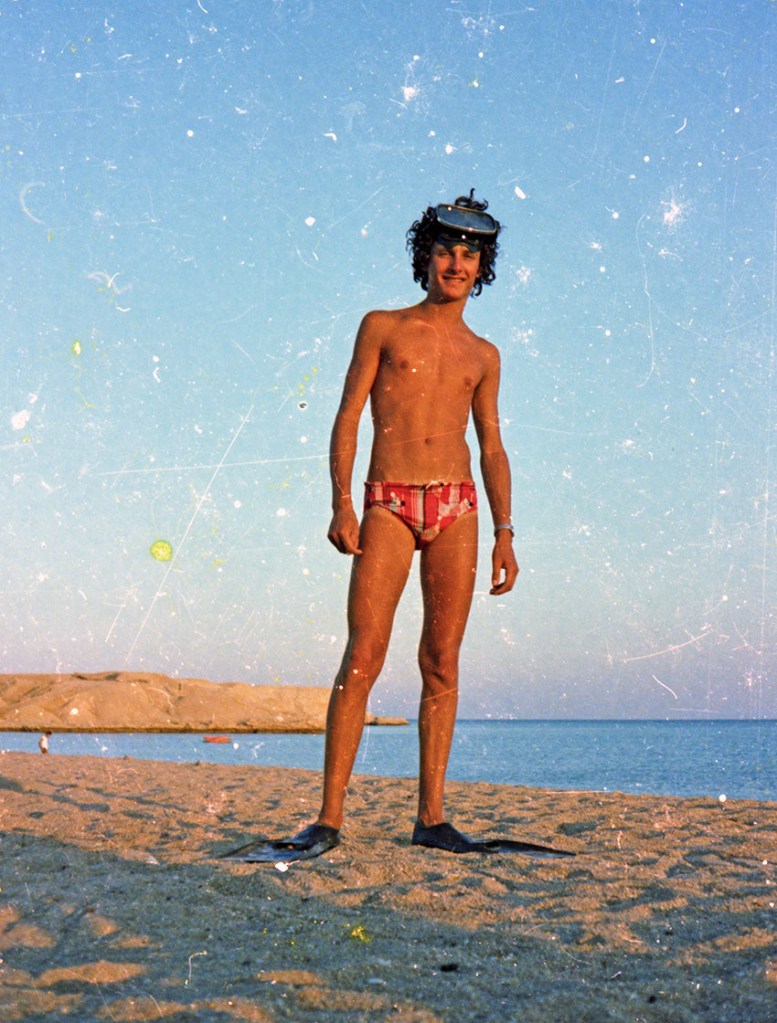

These days, most travellers associate the Sinai primarily with its exotic beach resorts and scuba diving and snorkelling. And little wonder, as the peninsula is blessed with a sublime coastline both above and beneath the waves. Even now, the beach at Dahab remains the most beautiful I have ever seen, and the Sinai’s coral reef―as regards accessibility and quality―is a match for any other in the world.

But for me, from the moment we passed through Eilat and entered the peninsula its superlative watery attractions notwithstanding, the feature which most grabbed my attention was the equally extraordinary landscape. The combination of desert plains and craggy mountains in a myriad of different colours; from white, to golden ochre through deep umbers and sienna, and culminating in blues and purples, was simply astonishing. The changing light; the chromatic sunrises; the intense sapphire of the day and the copper-tone sunsets reacted with the multi-surfaced sand and rock, presenting an optical feast of shifting tones and colouration.

In the south of the Sinai Peninsula in particular it was easy to see how its awesome visual dramatics gave birth to Yahweh―the eventual supreme divinity of the Israelites, and which would gradually evolve into the monotheistic Judeo-Christian concept of “God”. And funnily enough, of all the many remarkable aspects of the Sinai, the one which struck me most had an appropriately biblical reference: I recalled, even back then, the passage (Exodus 19:12) where Yahweh warns the Children of Israel not to touch the sacred mount (Mount Sinai / Horeb) “or they shall certainly die”. Until witnessing for myself the “biblical wilderness”―familiar then, only with the mountains of Europe which have nothing like defined parameters, but rather evolved from their neighbouring foothills which themselves slowly emerged from undulating plains―I had always found that to be an odd warning. I even recalled as a child in Synagogue on a Saturday morning, when first reading the relevant passage, asking my grandfather how the poor Israelites were supposed to know where the sacred mount began. But now, looking at the actual mountains of southern Sinai, thrusting forth from ironing-board-flat plains like brooding icebergs above a gravelly, sandy ocean, I could immediately attest to the voracity of the biblical author’s knowledge of the geography he was describing. And it sent a shiver down my spine.

Presented here are a handful of the dozens of photos I took on that trip with my old Cannonet 28 on high-speed Ektachrome film. Sadly, most of the transparencies were too damaged to convert, but I think these few, in their raw, scratched and grainy condition, begin to convey to sheer wonder of what we saw on that wonderful trip to that “great and terrible wilderness”.

Finally, and on a lighter note, I recommend viewing these images to the sound of America and their iconic track The Horse With No Name . This song became a kind of unofficial anthem to our trip, and thus the adoptive name of our trusty little Fiat…