BLOOD, SWEAT AND TOIL IN THE AXARQUIA*

Having just returned from another fortnight stint working our finca in the Axarquian mountains, sporting our latest collection of cuts, bruises and aching muscles, I was reminded of the wise words that head this post, uttered by the late lamented Fred, an early, fellow British, expatriate neighbour.

Fred, a taciturn Yorkshireman, when he did offer his rare nuggets of wisdom, had an uncanny way of getting right to the heart of the matter under discussion, and never were his few words wiser or truer than when he coined the now famous phrase (famous in our neighbourhood at least!), “Spain ‘urts”.

What many tourists and visitors to the region might not appreciate, in awe as they are of the stunning landscape of Andalucía, is that the agricultural land itself is mostly rocky, jagged, prickly and generally unforgiving for those who have to work it. Moreover, while the soil is often fertile, it is a fecundity requiring arduous effort to extract, and if Andalucía in general, is hard country to farm, then the mountainous slopes of the Axarquia often verge on the impossible.

This is why most of the agriculture of the region was for centuries, the exclusive domain of those both sufficiently hardy, and expediently motivated – or, in other words, the local peasant citizenry of the dozens of pueblos blancos (white villages) which dot the countryside like so many bleached apiaries. And like bees, these small, tough, resourceful workers would leave their village hives for the summer months and move into their finca homes, to tend their vines, pick their crops of grapes and nuts, dry their raisins, and finally, before returning to their pueblos, make their strong, sweet, fortifying mountain sacs.

Finca’s (privately owned small farms, or small-holdings) are dotted across the countryside in a seemingly random and chaotic, ill-fitting jigsaw of orchards and vineyards, that reflects the interminable division of parcels down the generations, from fathers to sons and mothers to daughters. In 1991, when we (and Fred) moved to the area, fincas were still a major source of self-employment and income for much of the Spanish agrarian working class, and being a “bueno campesino” (a good peasant farmer) earned one a measure of respect within the tight-knit pueblo communities.

But as Fred implied, this might have been an honourable life, but it was also painful and unforgiving. Hence, and quite understandably, as Spain softened and modernised, the attraction of the “campo life” dramatically decreased for the children of the pueblos whose gaze strayed hungrily to the newly flourishing cities and towns, with their universities, and their opportunities of well-paid work and rewarding careers.

This changing demographic is nowhere more starkly illustrated than in our own locality, where the vineyards, raisin-drying beds and almond groves are steadily disappearing, and the old finca cottages are either left to crumble back into the landscape from which they emerged, or are converted into tourist b&bs. Dido and I, together with an aging and dwindling generation of mostly 60-somethings are rapidly manifesting as living relics, as we continue to brave the constant cuts and bruises, the back-breaking tending of vines and trees, wasp stings, and extremes of weather (hot and cold, dry and wet).

What happens when we are all gone is already being mapped out, as the valleys, and easier lower slopes, are all being transformed into fashionable, low maintenance and lucrative plantations of avocado and mango. (The fact that these new “super crops” require hugely greater volumes of water to flourish than the traditional crops and that they are a disaster waiting to happen, is whole other story…)

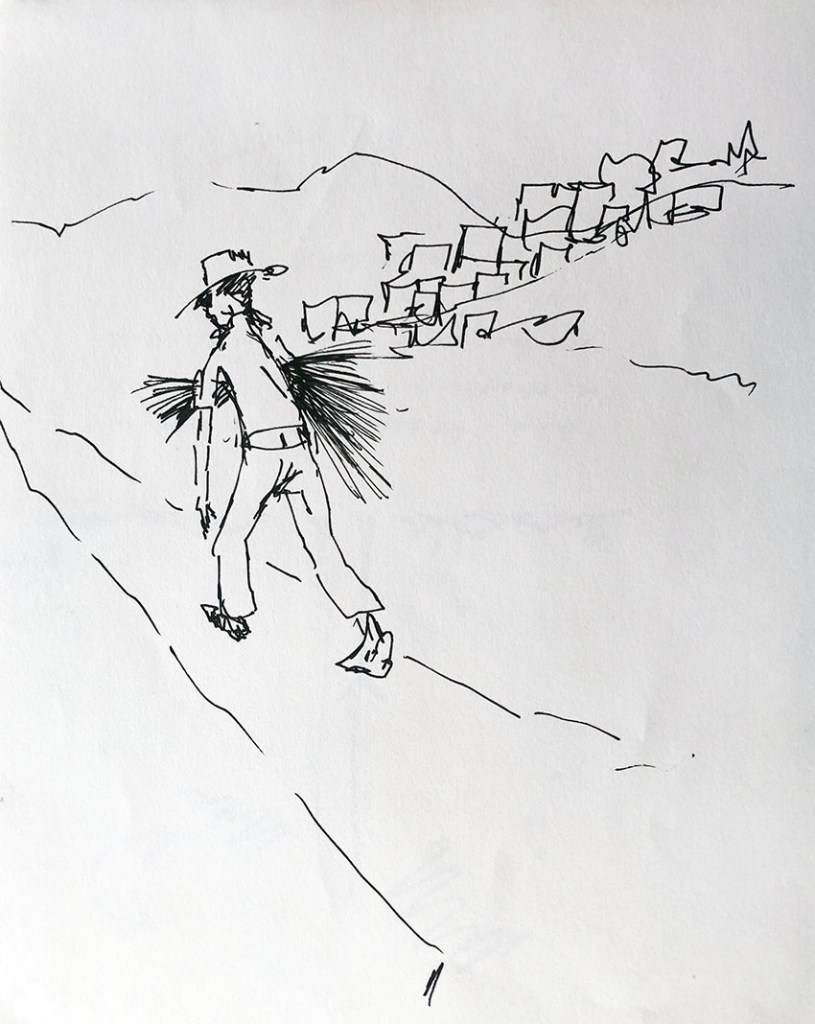

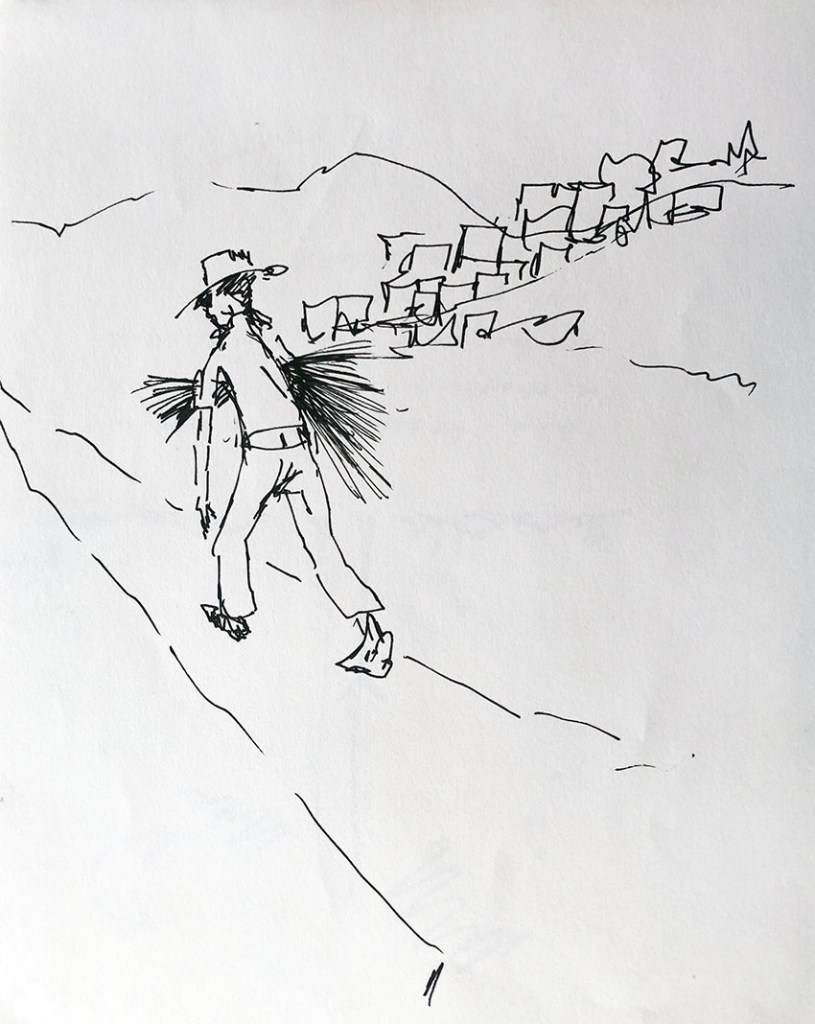

My drawings of campesinos displayed here were done during our first summer at our new home, in 1993, and are a reminder of how things used to be, when Spain (at least our part of Spain) really ‘urt…

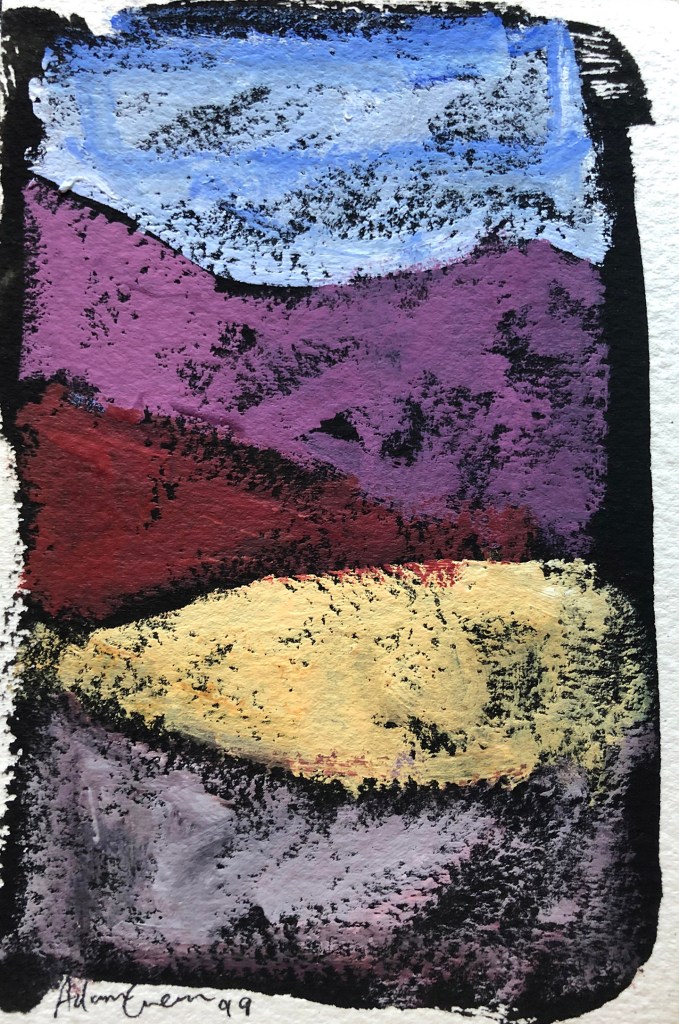

- Header photo is a panoramic view of the campo as viewed from our finca – looking south-east – in 1993.