…and getting things in proportion

Since the coronavirus crisis has taken hold, like the editors of The Archers*, I’ve been agonising over whether or not I should keep this a virus-free zone? Then, as often happens to me when planning these pieces, I was distracted / motivated by something unexpected.

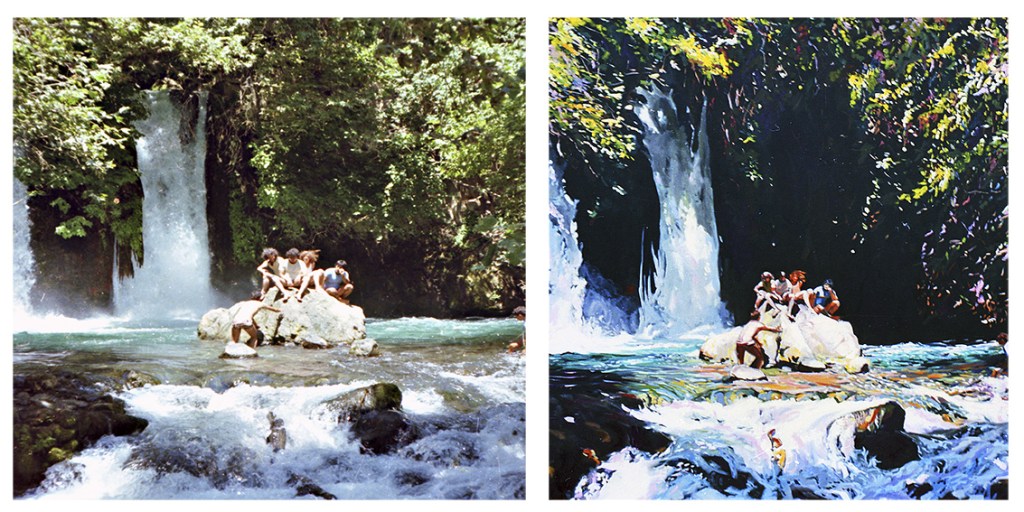

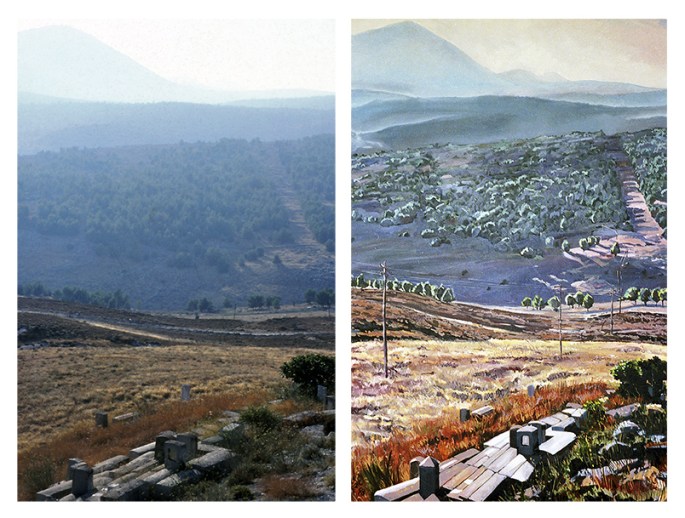

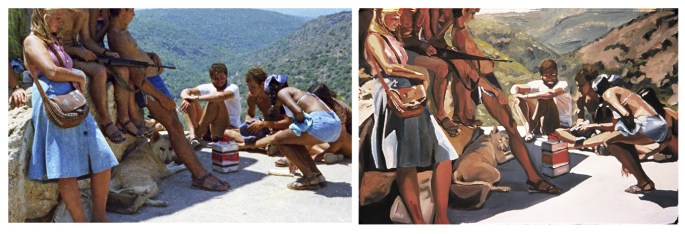

In this case I was mulling over whether to do another art-related post, versus a new recipe, when my attention was caught by a tiny, long-forgotten, ancient photo of my maternal grandparents working in their grocery shop. The photo was on top of a pile of similarly old and decaying pictures I’ve been in the process of digitising for posterity. All the photos are personally fascinating to me in their own different ways as they offer tantalising, often deeply atmospheric glimpses of my family’s history since their arrival on these British shores.

However, the thing which was different, and instantly relevant about this particular, overtly unremarkable image, was its remarkable context. For, what on the surface is simply a scene of ladies shopping at the local grocer’s is actually, ladies shopping at a grocer’s in the Mile End Road of London’s East End in the January of 1941. Anyone reading this with any semblance of knowledge – British or otherwise – will realise that this was at the height of the London Blitz, when thousands of bombs were being dropped on Britain’s capital on a nightly basis.

My point is not to minimise the current crisis, or to suggest we carry on “cautiously regardless”, as my grandfather and his customers did during the Blitz (for one thing, then they were being driven together, while today we are being urged physically apart). Rather, I am simply pointing out that many of our parents and grandparents went through far worse and more dangerous times than we are today (over 40,000 British civilians were slaughtered by the “Nazi virus” during the four months of the German raids on Britain’s industrial cities in 1940 and 41).

It’s the very ordinariness of this scene therefore, which makes it so eloquent, and to my contemporary eyes at least, all the more instructive, especially given the moment in history we are living through today. And although, as my grandfather often told me himself, the famous “Blitz Spirit” wasn’t quite all it was cracked up to be, there was sufficient determination, good humour, common sense and sheer guts among the majority of the people to ensure the nation survived the German onslaught relatively unscathed.

It shouldn’t be any different now…………………………..

*For most (but my no means all) of my non-British followers, The Archers is a soap opera, broadcast daily, on BBC Radio 4 continuously since 1951, making it the world’s longest broadcast soap.